The Pity of Torture

The Parliamentary expenses scandal has soaked up British airtime like a sponge. Admittedly, it’s not entirely the fault of the media: some of the tidbits are simply too juicy to ignore. It has everything: vanity, flamboyance, greed and silliness. It makes a Monty Python farce look tame.

The Parliamentary expenses scandal has soaked up British airtime like a sponge. Admittedly, it’s not entirely the fault of the media: some of the tidbits are simply too juicy to ignore. It has everything: vanity, flamboyance, greed and silliness. It makes a Monty Python farce look tame.

However, this has obscured an even more important debate going on in America at the moment. An unprecedented tug of war is in progress between the present Administration and the former one: the issue at hand is the use of torture. Dick Cheney seems to think that it’s is a good thing; President Obama disagrees. Cheney persists, Obama refuses to desist. This struggle has a familiar echo; it reflects an argument that I’ve had with my countrymen about whether or not torture is appropriate.

Some believe that the “techniques” utilised by the American military are not torture. Let’s take “waterboarding”, for example: this is a procedure whereby the prisoner is made to experience the sensation of drowning. Anyone who ever accidentally got water in their lungs while swimming should have an inkling at how unpleasant this can be: now imagine if it was done intentionally and in greater volumes. Saying this is not torture is a feat of verbal gymnastics that hasn’t been attempted since Bill Clinton tried to redefine the meaning of “is”.

The question then, is not if torture happens, but is it effective, and should it be used in the first place. Here history can guide us, and what it has to say is not particularly comforting for Cheney and his defenders: torture has rarely been used as an instrument of extracting truth, rather it has been more often utilised to get people to confess to things which they have not done.

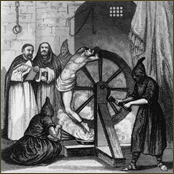

The Spanish Inquisition springs to mind as a primary example: from approximately 1480 to the age of Napoleon, it had the task of purging Spain of its religious diversity, targeting Jews, Muslims and Protestants, as well as punishing other offenses to the faith such as homosexuality. Torture was part and parcel of the Inquisition’s work: it was used to pressure recalcitrant prisoners into confessing their heresy or converting on the spot, in spite of the fact on a purely criminal basis, they had done nothing wrong; as denunciations were done in secret, it was commonplace for entirely innocent people to be swept up into the madness.

Among the techniques used by the Inquisition to extract confessions was the toca, which was an early form of waterboarding; prisoners had a cloth shoved into their mouths and liquid was spilled in until they choked. In our present age, we cringe in horror at their work: the kangaroo courts of the auto de fe, the use of the rack, and pulleys stringing up innocent people all in the name of fanaticism rightly inspire revulsion. It took Napoleon and his imposition of a new monarch on Spain to rid the country of the Inquisition entirely; by then, Spain was the model of a repressive state. It is telling that one of the more successful bits of humour in “A Man for All Seasons” is the repetition of a line by several English notables, “This is not Spain, this is England”, a statement whose ironic implications hint at the ingrained tyranny prevalent on the Iberian peninsula.

A more recent and perhaps more powerful example comes from the Soviet Union. In 1934, the party boss of Leningrad, Sergei Kirov, was assassinated by a lone gunman; the assassin was likely acting on the orders of state security, as Kirov was perceived as a rival to the then General Secretary, Josef Stalin. This event ignited a series of purges within the USSR, during which innocent citizens were accused of complicity in this particular murder, or subscribing to a wider plot instigated by Stalin’s rival in exile, Leon Trotsky. Millions were caught up by the rolling machine of terror: tortures used by the security forces included a novel method which utilised a rat, a heating plate and a chamber pot. The rat was put into the pot, and the pot was put on the heating plate. The prisoner was then forced to drop their trousers and sit down on the receptacle. The rat, obviously starting to cook to death, would become very frantic in its efforts to get out, thus attacking the prisoner in a most sensitive place. Other tortures used by the NKVD, the KGB’s predecessor, included beating prisoners on the base of the spine (in effect, the sciatic nerve) with a rubber truncheon, which causes an explosion of pain in the victim’s head, and applying pressure with the toe of a boot to a prisoner’s scrotum. All this was done in order to make prisoner’s confess to belonging to phony conspiracies of which they would have only had marginal awareness, and as a prelude either to years in a Siberian work camp, or to being executed.

If we look at other regimes, such as the Duvalier regime in Haiti, or Mobutu in Zaire, or the present junta in Burma, we find that torture is an instrument of compelling the innocent, not the guilty. Pain is there to make the unwilling agree to the absurd, not to tell the truth. Yet we are supposed to believe that merely a change in scenario and a difference in government is supposed to make this fundamental feature of torture disappear, as if by magic.

Worse, the use of torture undermines American power. Those who believe in its use may be under the impression that it is only through the ruthless application of physical force that power is secured; wrong, reputation is power too. America, unlike many nations, was not born out of an ancient ethnicity or a mere accident of history: rather, it was founded deliberately on an idea, which is summarised by Thomas Jefferson’s exquisite phrase: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, among them are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness”. The Declaration of Independence, from which this segment is extracted, goes on to list the presence of standing armies in America as being objectionable: torture is so out of the question that it doesn’t enter the moral universe of this document. It was these ideals in application that inspired the French Revolution, and cascaded throughout the world as an extension of man’s conscience. It may sound like a cliche to talk about “truth, justice and the American way”, but up until quite recently, this idea had resonance. By adopting torture, America has walked away from these ideals in the name of perceived realpolitik. Indeed, America has turned the ideas upon which it was founded into an elegant hypocrisy…and who takes what a hypocrite has to say seriously?

The proponents of physical coercion may counter, all right then, if we give up torture, then what do we do? The answers are relatively straightforward: bribery, psychology and religious argument. All three do not require the use of physical force, and if done correctly, will get at the truth rather than what the torturers want to hear.

Bribery is perhaps the most simple; not every man has a price, but many do. And bribery need not be in raw cash terms: it can be the education of one’s children, a promise of safe asylum, the establishment of a new life. Incentives can be linked to accuracy of information.

Psychology should not be understood as therapy. Rather, there is nothing wrong with giving a prisoner the false impression that they are talking to someone they can trust, or they are in circumstances whereby they feel they can speak the truth. This requires staging of a situation, creating beliefs which are not necessarily true, and then analysing the results.

Religious argument is perhaps the least understood method. There is an assumption from the media’s images of Islamic fananticism that somehow it is a religion of ignorance rather than knowledge. Nothing could be further from the truth: many of the Islamists are to their faith what televangelists are to Christianity. They deal in short, punchy messages which lack depth, resonance, history or thought. Words mean a great deal in Islam: it was the poetry of the Qu’ran which attracted its first followers; it is no coincidence that much of Islamic art involves calligraphy through which the word of God is repeated. A typical Sufi scholar has the intellectual and theoretical capability to make the average terrorist hothead bleed out the ears; if convinced that they are actually going against God, Muslims have an obligation to correct the error as quickly as possible.

All three methods, however, are less “macho” than just simply whacking the terrorist on the head or making him think he’s drowning. There is a mistaken belief among some that physical violence somehow equals masculinity, and thus supporting torture is the “manly” thing to do. It is, rather, an admission of weakness: i.e., one feels the need to assert force in order to “prove something” as one couldn’t think a way out of a problem. Given that America was founded by thinkers, this situation is likely causing consternation to the likes of Jefferson and Madison in the afterlife. The pity of torture is that whatever the perceived gains are, they are not outweighed by the costs. Fortunately, however, the President appears to understand this concept better than his detractors. While the process of rehabilitation is unlikely to be straightfoward, at least it’s in motion.