In Liverpool

This blog post is being written as the sun is setting over the Mersey. Outside my hotel room window, I can see the last hints of orange and pale blue fade out on the horizon: the streetlamps are lit, there is a distinct chill in the air. Another day is over, and the city is gently falling asleep.

This blog post is being written as the sun is setting over the Mersey. Outside my hotel room window, I can see the last hints of orange and pale blue fade out on the horizon: the streetlamps are lit, there is a distinct chill in the air. Another day is over, and the city is gently falling asleep.

I am here, which is far away from my usual place of residence, due to a business trip. I have never been to Liverpool before; this is rather a pity as I had sentimental reasons for visiting. For example, after leaving University in the early 1990’s, I worked for a technology company which sadly no longer exists. In order to go to my office or on the myriad trips that the company required, I was required to do a lot of rail travel: my companions on these journeys were my books and my portable CD player. Invariably the latter contained a Beatles album. I am not entirely sure how my passion for their music began, but to this day, I can still quote lyrics from memory and recognise most of the songs. Humming tunes from “Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” helped me to stay sufficiently calm in order to pass my driving test. Strawberry Fields and Penny Lane are forever in my ears and in my eyes.

I had another reason to want to come: I also relish the works of Alan Bleasdale, who wrote about Liverpool’s turmoil during the Thatcher era, first in his famous tele-drama, “The Boys from the Black Stuff” and later in “GBH”. Bleasdale’s Yosser Hughes (from “The Black Stuff”) remains an iconic figure, his desperate plea for employment (“Gissa job!”) symbolic of how many in Liverpool felt during the crushing recession at the beginning of the 1980’s. “GBH” featured Michael Palin as a sincere, kindly schoolteacher who was up against a far-left faction (and its far-right puppetmasters) which was unmistakably a poke at both the Tories and the Trotskyite Militant Tendency.

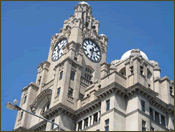

Liverpool, of course, is a dynamic, evolving place, and is neither defined by the black and white world of the early 1960’s nor the blight which scarred it nearly 30 years ago. Time has moved on. There are many grand buildings which indicate what a rich city it was when it was the centre of the world cotton trade, but they’ve been updated. For example, I went to a meeting at the Royal Liver Building, perhaps the city’s most recognisable landmark. Based upon its grand facade, I suspected I’d find within creaking oak floors, marble staircases and an old fashioned elevator, the kind which is like an brass fringed iron cage. Instead, the interior of the building is fully modern, the lifts were operated by a touchscreen which allowed one to select which company one wanted to visit rather than simply pushing a number. The offices themselves were climate controlled and double glazed. The coffee was adequate. This is better. Yet, somehow it felt wrong.

After my meetings ended, I went in search of the Cavern. I found what remained of it on Matthew Street; it’s long gone, replaced by a nine-level building. A sign states where the entrance once stood. A facsimile of the club is a few doors down. A rather unconvincing statue of John Lennon looks cooly on. It’s progress, presumably, from a time when the streets were dark and dirtier and less prosperous. Yet somehow I wanted the excitement that greeted the striking new sounds from the four lads. It’s disappeared, replaced by a tourist trap: what I saw simply didn’t inspire.

Theoretically, progress isn’t supposed to stir mixed emotions. However this is precisely what I feel while I’m here. It is the same sensation I felt when I watched BBC Parliament replay the February 1974 election night broadcast. As the results were listed, the newsreaders identified various constituencies as being centres of the “steel industry” or “coal mining”. They aren’t any longer. Yes, in a sense, things are better given that people are no longer exposed to the dangers of digging coal out of the ground, and working at a desk in the Royal Liver Building is probably more pleasant than turning iron ore into steel, yet somehow it feels not entirely right. We lost something; our present era may be forcing us to confront what we left behind.

Britain is now a post-industrial nation in most respects; despite some world-class firms like Rolls Royce (I refer to their aerospace division), it is not the “workshop of the world” any longer. We put our trust in financial services: now that has proven to be folly, we are looking around, trying to find something else to do, something else to sell. Information technology is one possibility, but it is not a solution which provides mass employment and remains highly competitive. We cannot simply go back to manufacturing, as the skills were lost after the factories shut and the industries crumbled into the dust. We are going to have to come up with something else: green technologies may offer an answer. However, that will require research, and the government is showing little sign of wanting to fund more of this, despite the fact that two University of Manchester physicists just won the Nobel Prize for their work with graphene, a new material which is a successor to carbon fibre. Rather, this government appears to be content to summon up the spectre of Yosser Hughes once more and to leave him to his fate.

Liverpool previously revived because a lot of government and academic money flowed its way: for example, the Home Office has a substantial presence here. I had a walk through the city campus of Liverpool John Moores University, which seemed to be modern and buzzing. I noticed also that the universities’ common pension scheme has their head office at the Royal Liver Building. Given the new era of austerity, and the pompous manner in which the resulting changes are being presented by the Conservatives, Liverpudlians should be terrified about what the future may bring. I didn’t see any evidence of this. Rather, from the taxi driver who picked me up at Lime Street Station, to the receptionist as the company I’m here to visit, I have been treated with kindness and courtesy. The receptionist saw that I was a bit out of sorts after my long journey and treated me as if she were my Scouse grandmother. Usually anxiety doesn’t translate into cheer, let alone niceness. But perhaps after all that Liverpool has been through, its citizens have developed a thicker skin than most. The disaster that sometimes masquerades as “progress” or “change”? Been there, done that: it’ll come right one day. Maybe they’re right: I certainly hope so.