Following Thomas

[AMAZONPRODUCT=B000P5FH4Y]

Last Saturday, PBS ran a documentary about the Mormons. Lasting in excess of 270 minutes, it detailed the history of the faith and its long struggle to fit in with the rest of America. One of the historians appearing on the programme remarked on how peculiar this epic may seem on the surface: after all, he stated, Mormons were exclusively white at the beginning and mainly Anglo-Saxon. Furthermore, Mormons tended to be hard working and community minded. Nevertheless, their history is one of being shifted onwards by communities and states which rejected them until they landed in Utah.

I don’t share the Mormon faith; personally, I think it’s wildly ahistorical to suggest that Jesus Christ ever set foot in America. However, we all go through life believing in things which are difficult to prove or are in fact absolute fiction: if you’re an athiest, you may want to reach into your wallet at this point and look at what banknotes you possess. The fiction you believe in is inscribed on the money: the central bank issuing the pounds or dollars promises to pay the bearer on demand a particular sum. But a particular sum of what? Actually, it’s nothing: the only value it has lay in belief. Our society simply couldn’t function without items like this, i.e. that which cannot be proven or fulfilled.

Even so, Joseph Smith struck me as an odd sort of prophet. For example, upon arriving with his flock in Nauvoo, Illinois, he apparently more or less established a Mormon government. He took it upon himself to become a general and even ran for President. To an outside observer, this doesn’t look like St. Paul’s dictum which suggests “Not me, but Christ in me be magnified”. But then again, Constantine the Great and the Byzantine Emperors which followed him tried to associate themselves with the Apostles, and Islam’s early years were punctuated by a crisis of authority, so perhaps such an interweaving between political and religious power is not all that far-fetched. It’s not appropriate, however, in a nation that prides itself on separation of church and state; deviating from this deeply held principle earned Smith and the Mormons the opprobrium of their neighbours.

Also, I found the whole business of being a Mormon missionary rather disquieting; the documentary showed two very earnest young men speaking to people on the streets of an unidentified city. There was nothing particularly nasty about it, it was just intrusive; the rhythms of the city and its inhabitants turned staccato as they interrupted. The young men were polite and respectful, but they possessed a certitude which was unnerving. Faith in many respects is a personal journey; surely the Almighty possesses the ability to speak to us all on an individual level? Was it really necessary to go up to random individuals and talk at them? I can recall occasions when I’ve been walking along a similar city street, my thoughts weaving together into a story or a poem and then having the delicate fabric torn asunder by such intrusions. Yes, I love God, but among the gifts he granted was my ability to think: surely I praise Him better by doing that rather than fending off his supposed messengers.

Beyond this, an interview with the South African born artist Trevor Southey was disturbing. You cannot be homosexual and Mormon, and Southey did his best not to be the former so he could continue to be the latter. He married and had children. This was not a sustainable situation; he eventually divorced and his wife had him excommunicated. The pain in Southey’s eyes was evident as he stated that he wanted a religion that was going to accept him as he was constituted, be that as it may outside Mormon norms.

I didn’t care for Mormon excommunication. The documentary explained how deviation from doctrine basically slammed shut the door of heaven on a number of scholars; what struck me as particularly odd was an interview with one researcher who said that the people excommunicating her shook her hand afterwards.

Finally, I was upset by the historical racism in Mormon doctrine. Up until 1978, people of colour were not entitled to receive the Priesthood in the Mormon faith. The change in policy seems to have come rather late in the day.

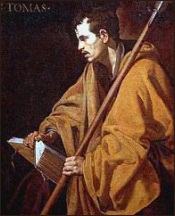

After I switched off the television, I couldn’t help but think of Mitt Romney. I don’t think it would be useful or even particularly American to question his religion; however, as we’ve discovered, the interests, character and morals of the President do inform his decision making. Bush believed in his own righteousness, and that God was his co-pilot. We have seen the results of his being too certain: violence, death, destruction, destitution. President Obama has been quieter and has been much more willing to embrace doubt: as his position on marriage equality has shown, his thinking evolves rather than is set in stone. If Bush carried the sword of the crusader, President Obama walks alongside the Apostle Thomas, who first questioned the Resurrection, and indeed refused to believe it until he saw Christ’s wounds. For example, I understand that President Obama wasn’t keen on the slogan “Yes, we can” at first; this may have been due to the simplicity of this message being incongruous with a complex world. But just perhaps Thomas was tugging at his elbow. Does Romney want to emulate the example of this less celebrated apostle or does he adorn the general’s uniform and the unabashed certainty of Joseph Smith?

Certainly, Mitt Romney’s positions have changed over time, but these shifts seem more to do with securing advantage rather than an exploration of Thomasian doubts. But we want a Thomas in the office, the one who is sceptical at first glance, checks his facts, but once he is secure in knowledge, carries on to quiet achievement. Thomas is reputed to have covered a greater area than any other apostle, including Syria, Persia and India; he was the only one to preach outside the Roman Empire. In 52 AD, he landed in what today is Kerala, South India and established “Seven and a Half” churches. Even there, Thomas remained doubtful: according to a 3rd century scripture called “The Acts of Thomas”, Christ commanded him in a dream to take his mission to two kings in India, one in the north, the other in the south. Thomas refused and God had to arrange circumstances by which he fulfilled his charge, gathering many converts in the process. Yet Thomas barely gets a look in at any Sunday School; the Syriac “Acts of Thomas” are not part of accepted scripture in most Christian churches. Not for him high praise or grandeur, just the occasional work of art and some quiet rememberance. Who would want to follow Thomas? Who in the pursuit of high office and the exaltation of self that implies would want to emulate his example? Who wants to suggest that doubt is a virtue, and that being too certain implies fatal hubris? In both America and on this side of the Atlantic, we are plagued with people in leadership positions who tell us that there is no alternative and that it’s their way or the highway. But one can follow Thomas and sail in a different direction, remain with faith and yet sit alongside doubt. This embrace of uncertainty could be called prudent in a world that seems more full of data than it is imbued with wisdom. It may or may not sit well alongisde Romney’s Mormonism; quite frankly, I’m not sure.

Certainly, Mitt Romney’s positions have changed over time, but these shifts seem more to do with securing advantage rather than an exploration of Thomasian doubts. But we want a Thomas in the office, the one who is sceptical at first glance, checks his facts, but once he is secure in knowledge, carries on to quiet achievement. Thomas is reputed to have covered a greater area than any other apostle, including Syria, Persia and India; he was the only one to preach outside the Roman Empire. In 52 AD, he landed in what today is Kerala, South India and established “Seven and a Half” churches. Even there, Thomas remained doubtful: according to a 3rd century scripture called “The Acts of Thomas”, Christ commanded him in a dream to take his mission to two kings in India, one in the north, the other in the south. Thomas refused and God had to arrange circumstances by which he fulfilled his charge, gathering many converts in the process. Yet Thomas barely gets a look in at any Sunday School; the Syriac “Acts of Thomas” are not part of accepted scripture in most Christian churches. Not for him high praise or grandeur, just the occasional work of art and some quiet rememberance. Who would want to follow Thomas? Who in the pursuit of high office and the exaltation of self that implies would want to emulate his example? Who wants to suggest that doubt is a virtue, and that being too certain implies fatal hubris? In both America and on this side of the Atlantic, we are plagued with people in leadership positions who tell us that there is no alternative and that it’s their way or the highway. But one can follow Thomas and sail in a different direction, remain with faith and yet sit alongside doubt. This embrace of uncertainty could be called prudent in a world that seems more full of data than it is imbued with wisdom. It may or may not sit well alongisde Romney’s Mormonism; quite frankly, I’m not sure.