Badly Breaking

Recently, I was introduced to the television series “Breaking Bad”. I’m not 100% sure why this had passed me when it was originally on the air; perhaps the hype surrounding it had the effect of blunting its appeal.

Recently, I was introduced to the television series “Breaking Bad”. I’m not 100% sure why this had passed me when it was originally on the air; perhaps the hype surrounding it had the effect of blunting its appeal.

Nevertheless, it is an epic programme. The anti-hero of the show, Walter White, is a chemistry teacher who is diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. He decides that the only way to pay his medical bills and secure his family’s financial future is to go into the business of making and selling methamphetamines. His chemistry skills ensure that his product is highly sought after; the sordid business of drug trafficking leads Walter to make ever worsening choices, turning him from a good (if somewhat dull) and mild mannered man into a master criminal. It is a morality tale which suggests that we become either good or evil not necessarily because we are born a particular way, but because of the choices we make.

However, it is worth re-examining the pivot of the story: Walter needs money to stay alive and provide for his family. He only finds out how ill he is, despite suffering from a persistent cough, after he collapses at his second job at a car wash. He’s whisked away in an ambulance to a nearby hospital: yet, he is so concerned about the cost that he asks the medic to drop him off at a street corner despite the fact that he is semi-delirious and can hardly breathe. Walter’s wife later arranges for him to see a specialist, she pays for the exorbitant initial consultation with a credit card; later, the cost of his treatment is estimated at $90,000, and as this is not covered by his dismal insurance policy, he is left to foot the bill. There is no indication of compassion on the part of the doctor, rather, the choice presented is “pay up or die”. This is the logic of a racketeer, not a physician.

In short, it is money which is the distorting factor in this story. It is money, and the lack thereof, that warps Walter’s values to the point he transforms from a person whose main purpose in life was being an educator into one whose trade is chemically induced misery and early death. He feels compelled to make a choice between himself (and his own) and the nameless consumers of his product. He has decided that the good of his community can go hang, he needs the cash.

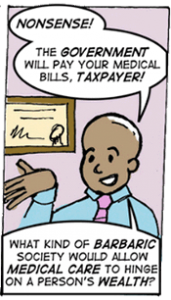

A cartoon which appeared on Buzzfeed brought home how easily a different set of policies could have easily changed the outcome of Breaking Bad’s story: it was entitled “Breaking Bad Anywhere But US Edition”. An alternate Walter is given the same diagnosis and expresses his fears that his family will be bankrupted. The doctor tells him not to be ridiculous, that the bills will be paid by the government as he is a citizen and a taxpayer. The alternate Walter expresses relief and decides to return to teaching chemistry.

A cartoon which appeared on Buzzfeed brought home how easily a different set of policies could have easily changed the outcome of Breaking Bad’s story: it was entitled “Breaking Bad Anywhere But US Edition”. An alternate Walter is given the same diagnosis and expresses his fears that his family will be bankrupted. The doctor tells him not to be ridiculous, that the bills will be paid by the government as he is a citizen and a taxpayer. The alternate Walter expresses relief and decides to return to teaching chemistry.

It is a pity that many governments, including Britain’s, fail to see the point: if everything in life becomes a cash transaction, then money may become more important than the society it intends to serve. At the moment, we are seeing creeping privatisation of the National Health Service. Private companies are invited to bid for contracts to provide many public services, the most notorious of which is Atos, whose task has been to try and squeeze people out of their disability benefit. This has reached absurd lengths, including a blind woman being asked how many fingers the assessor was holding up. It’s clear that the consideration of Atos’ bottom line was more important to the assessor than actually treating the person in front of him as someone with a genuine disability.

Money has also been deemed more important than public safety. It was recently announced that Humberside Police is to cut 700 jobs, 200 of which are officers, in order to save £31 million. The new shift patterns which are likely to take hold may lead to additional sickness and fatigue among police officers, thereby less effective law enforcement.

The situation has gotten so dire that they stir the memories of those who remember when there was no welfare state or public health care system. Harry Leslie Smith, a 91 year old activist, warned the Labour Party conference that there was a danger that our “future will be my past”: and his past was one in which cancer patients screamed in pain because they couldn’t afford morphine, and his sister died in agony at the age of 10 due to tuberculosis because Harry’s parents couldn’t afford medical treatment.

Back then, a time which Harry referred to as “uncivilised”, money held the same totemic force that it does now. All of life’s ambitions, all that one could hope or dream, was dependent upon lucre’s acquisition and preservation.

Earlier this year, I was part of a Labour Doorstep event, in which myself and another activist went from house to house along a suburban Bradford street and asked voters what their concerns were. One elderly lady, clearly infirm but nevertheless residing in a reasonably comfortable home, told us of her fears about the NHS. She expressed disgust with the government, stating that “they think money is what life is all about”. We agreed with her. What is more, in retrospect, focusing solely on money is self-defeating. The cuts in Humberside’s police force may push crime up, and that has a cost to the exchequer and the large insurance companies he favours. The Atos assessments which are incorrect will need to be re-administered and revised, and that has a cost too. In the fictional universe of Breaking Bad, the cost to the state of cleaning up after those left damaged or dead by Walter White’s methamphetamines is also high, likely much higher than actually treating the man. But as it is with love, excessive pursuit of a thing can cause it to flee from you.

We should remember that money is supposed to be a tool, a medium of exchange that takes away the necessity of barter. It is not to be racked up like points in a video game, nor is it intended to be used as a means of domination against those who are weaker or less capable. Such a perspective leads back to Harry Smith’s barbaric world of the 1930’s in which cancer patients’ cries echoed down the streets lined with impoverished tenements, and those without means were dumped into anonymous paupers’ graves after death. Justice in this kind of environment is merely the good of the strong, and we are one financial catastrophe away from total catastrophe. Such a situation is not just breaking bad, but badly broken: leaving us fearful of the Walter Whites, the Atos assessor, the privatised company that will cut costs and potentially service in the name of the bottom line. Fortunately, we still have time to choose another path; fortunately, we can select a good society as easily as we can place a cross in a box at the next election. We can abandon a fetish, for that is what the love of money alone surely is, and choose a better life.