The Case Against Starbucks Capitalism

I don’t like Starbucks. But then again, I know what real coffee should taste like.

I don’t like Starbucks. But then again, I know what real coffee should taste like.

After I graduated from University with Honours in 1994, I was given a vacation in Kenya as a reward. I remember the morning after I arrived in Nairobi: the hotel’s dining room was painted a bright yet mild yellow, and was bathed in a golden equatorial sunlight that filtered in through a set of French doors. Coffee was brewing in a large copper and brass contraption that sat next to my table. It steamed and puffed like an old fashioned locomotive, churning and percolating its magic brew. When the cup was brought to me, I immediately got a blast of rich coffee scent. Intoxicating. I lifted the cup and took a sip.

There are some coffee snobs who compare the flavour of the beverage to wine in terms of complexity and depth; this was the sole instance in my lifetime in which the metaphor seemed justified. My eyes flew wide open and my mouth was awash with fresh tastes which hinted at chocolate, whiskey and a touch of vanilla. I sucked it down in one gulp and asked for another, and then another. This proved to be a mistake: the coffee fresh from a Kenyan plantation proved to have more caffiene than its stale, supermarket-bought counterpart. Fortunately, as a newly minted graduate, my over-exhuberance could be written off as a natural result of completing my course of study.

Starbucks, in comparison to that seductive Nairobi brew, tastes scorched beyond all recognition. I am reminded of how Bell Irwin Wiley wrote in his seminal work about the typical Confederate soldier, “The Life of Johnny Reb”, how sometimes the greycoats were obliged to burn peanuts to create a coffee substitute. Starbucks coffee tastes engineered to make one demand either a sweet pastry or sugary syrup to counteract its bitterness. On those rare occasions where there is no other alternative, I drink it, but with extreme reluctance.

Beyond providing a bad cup of coffee, however, Starbucks also provides an interesting example which shows much of what afflicts Western capitalism. The term “casino capitalism” has been used to describe the behaviour of the financial services industry. This phrase is accurate and illustrative: banks “bet” large sums of money on high risk investments, rather like a down and out gambler in Vegas taking another chance at the craps table; the difference being, of course, that the banks were using other people’s money rather than their own.

But what of the rest of the economy? What of the Wal Marts, McDonalds, Tescos and yes, Starbucks? Surely they do not fit the same “casino capitalist” mould – after all, many of these firms are still making money and they’re not directly “laying bets”. However, just because they are profitable doesn’t mean they’re not doing damage. Indeed, by looking in more detail at Starbucks rise, and subsequent problems, we can see many of the issues they create.

Starbucks began in 1971; at first, it was not a cafe. Rather, it sold coffee beans from a small outlet located in Seattle’s Pike Place Market. It was a rather bohemian enterprise; it had been founded by two teachers and a writer. In 1982, they changed emphasis and began to sell brewed coffee as well as beans. In 1987, the business was bought by the coffee shop chain Il Giornale, which subsequently changed its name to “Starbucks”. Since that time, it has been on a path of relentless expansion, putting outlets in places as far afield as Hong Kong. It later struck a deal with the book chain Barnes & Noble to provide coffee in its establishments, and has been doing so ever since.

We can see an arc in operation here: first, there was a small, local business, which was there to provide a decent living for its owners and to provide for local needs. Then, it was picked up by a larger company, which utilised its brand and humble origins to market a fantasy: namely, that each branch of a mass chain is somehow replicating the spirit, if not the intent, of the original. It then continues to penetrate the market to saturation point, even going so far as to infiltrate other large chains to spread its influence. But what is lost in the process is the dynamics which drove the success of the original: people liked the original Starbucks because they knew the owners and the owners knew their customers. The relationship meant that quality products were supplied. Because Starbucks is now a giant corporation, by definition it lacks the intimacy to maintain that link to the customer: rather, it is using its vast network to define what a cup of coffee should be. This is an inversion of Adam Smith’s ideas about capitalism; he stated in the Wealth of Nations that the invisible hand of individual needs and aspirations would drive the satisfaction of those demands by a responsive business sector; what he did not fully foresee, nor could fully foresee given his context, was a scenario in which companies had sufficient power to dictate what customers want and what they receive.

Indeed, Starbucks has been very aggressive, particularly in the United States, in obliterating alternative definitions of coffee. On visits to America, I have witnessed the curious phenomenon of seeing Starbucks very closely placed together: in less than one square mile, I saw four. Two were on the same block; albeit, one was inside a Barnes and Noble. The sole alternative within this area of suburban New York was a Dunkin Donuts: yet another chain, although it is not precisely competing in the same sector as Starbucks, which is apparently going for more “aspirational” customers.

In the process of destroying its heritage, Starbucks has attracted criticism along the way. Fair trade coffee only represents a portion of its offering, thus they help perpetuate the production of non-fair trade coffee and the poor working conditions this entails. A Starbucks in Beijing’s “Forbidden City” was closed in July 2007, due to Chinese objections: they felt that the company represented a divergence from the nation’s customs and heritage. Unions have had reason to complain as well; for example, in March 2008, Starbucks was ordered to pay $100 million in back tips to its employees, which the company had originally paid to shift supervisors.

However, all this grasping and expansion has led to an end nearly as bitter as the coffee they sell. In July 2008, Starbucks was forced to announce the closure of 600 of its outlets, due to oversupply. However, perversely, Starbucks has made it very difficult for another firm like its original self to emerge from the wreckage. The two primary losers are those who work at Starbucks as they will find their skills in a state of oversupply as well, and the customer, who will continue to be pushed a (purposefully?) inferior product.

If this phenomenon was merely confined to hot drinks, we probably could rest more easily. However, we see this scenario also when Tescos or other large supermarket chains push out the local butcher or green grocer. We also witness this process in operation when Wal Mart kills the local department store, and McDonalds knocks out the family diner. We lose quality, we lose locality, and we lose sensitivity, all in the name of brand status or price. It’s regrettable now that one can’t wander to Pike Place Market and find three idealistic entrepreneurs offering their roasted coffee. It’s lamentable one can’t drive to Vermont and find two hippies in a shed mixing their ice cream with care and creating batches of sweet creamy goodness of which no two will taste precisely the same. Perhaps the most damaging illusion that corporations sell us is that we can have this and even be environmentally friendly and ethical, despite the fact that their wares are mass produced and marketed.

Government can help, of course. It can change its policy mix to favour small businesses, and enforce tougher social responsibility and environmental legislation. However, it will lie with us, the consumer, to do something which doesn’t come naturally: embracing the inconvenient. We will have to go further to find the small local butcher, or visit the diner, or buy that individual mug of Joe. If we don’t, government measures will fail, as money will continue to invigorate the Starbucks of this world. If consumer behaviour does change, however, it may be possible to see a day bathed in less than equatorial sunshine where a cup of coffee can bring a smile to one’s lips rather than a wince and a poke in one’s conscience.

72 hours after

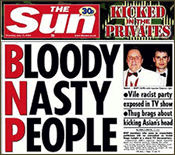

72 hours after  I’ve had the rare privilege of telling one of the leaders of the British National Party precisely what I think of him and his creed on national television. The occasion was several months ago, and it was on a BBC programme entitled “The Big Questions”; I was in the studio audience. I had to get up early on a Sunday morning to attend; it was surreal to drive to Southampton with the orange and purple colours of early dawn painting the blank canvas of the empty motorway. My mind protested the violation of the normal rhythms of the week. Surely, it told me, the best thing to do was to turn around, go back to bed, then wake up late, drink coffee, and read the Sunday papers. I did not expect that my presence would add much except an additional face to the crowd.

I’ve had the rare privilege of telling one of the leaders of the British National Party precisely what I think of him and his creed on national television. The occasion was several months ago, and it was on a BBC programme entitled “The Big Questions”; I was in the studio audience. I had to get up early on a Sunday morning to attend; it was surreal to drive to Southampton with the orange and purple colours of early dawn painting the blank canvas of the empty motorway. My mind protested the violation of the normal rhythms of the week. Surely, it told me, the best thing to do was to turn around, go back to bed, then wake up late, drink coffee, and read the Sunday papers. I did not expect that my presence would add much except an additional face to the crowd. Beating up on Gordon Brown has all the appeal of shooting roadkill. The corpse may be twitching still, but it is still a corpse: obliterating it further is unnecessary. The Prime Minister must know on some level that his time in office has been a tragic failure, an epic tale of ambition running ahead of ability.

Beating up on Gordon Brown has all the appeal of shooting roadkill. The corpse may be twitching still, but it is still a corpse: obliterating it further is unnecessary. The Prime Minister must know on some level that his time in office has been a tragic failure, an epic tale of ambition running ahead of ability. I probably didn’t buy my car from the most reputable salesman. He wore silver dice cufflinks, had a shirt that was so crisp with starch that the collar tips could be used to gouge someone’s eyes out, and had enough mousse in his hair to keep Vidal Sassoon in profit for a year. But beyond this, there was an aspect to his countenance which I simply could not trust: perhaps it was the insincere sincerity in his tone of voice or the false “hail fellow well met” demeanour. I could not shake the sense that there was something exploitative in every word he said.

I probably didn’t buy my car from the most reputable salesman. He wore silver dice cufflinks, had a shirt that was so crisp with starch that the collar tips could be used to gouge someone’s eyes out, and had enough mousse in his hair to keep Vidal Sassoon in profit for a year. But beyond this, there was an aspect to his countenance which I simply could not trust: perhaps it was the insincere sincerity in his tone of voice or the false “hail fellow well met” demeanour. I could not shake the sense that there was something exploitative in every word he said. There is a difference between anarchy and chaos. Anarchy implies people being in charge of themselves and willfully going in individual directions; in contrast, chaos is apparently defined by no one being in control of anything and everyone running around in circles. Britain got a large dose of chaos yesterday. On Monday afternoon, the Speaker of the House of Commons, Michael Martin, was expected to announce his resignation due to his role in the continuing expenses scandal. At best, he’s been the deaf, dumb and blind referee to how expense claims have been handled, and thus partially responsible for both frivolous and fraudulent bills being paid by the nation.

There is a difference between anarchy and chaos. Anarchy implies people being in charge of themselves and willfully going in individual directions; in contrast, chaos is apparently defined by no one being in control of anything and everyone running around in circles. Britain got a large dose of chaos yesterday. On Monday afternoon, the Speaker of the House of Commons, Michael Martin, was expected to announce his resignation due to his role in the continuing expenses scandal. At best, he’s been the deaf, dumb and blind referee to how expense claims have been handled, and thus partially responsible for both frivolous and fraudulent bills being paid by the nation. My introduction to the works of Samuel Beckett was botched. It occured in an undergraduate English course, whose purpose was to examine less than common texts, and sadly I had a less than common lecturer. Unfortunately, he was more fixated on talking about Freud’s ideas on children playing with their excreta (and how we’re actually supposed to treat faeces like Lego) than helping young minds to interpret the classic works in his care; among these was Beckett’s most famous play, “Waiting for Godot”.

My introduction to the works of Samuel Beckett was botched. It occured in an undergraduate English course, whose purpose was to examine less than common texts, and sadly I had a less than common lecturer. Unfortunately, he was more fixated on talking about Freud’s ideas on children playing with their excreta (and how we’re actually supposed to treat faeces like Lego) than helping young minds to interpret the classic works in his care; among these was Beckett’s most famous play, “Waiting for Godot”. The Parliamentary expenses scandal has soaked up British airtime like a sponge. Admittedly, it’s not entirely the fault of the media: some of the tidbits are simply too juicy to ignore. It has everything: vanity, flamboyance, greed and silliness. It makes a Monty Python farce look tame.

The Parliamentary expenses scandal has soaked up British airtime like a sponge. Admittedly, it’s not entirely the fault of the media: some of the tidbits are simply too juicy to ignore. It has everything: vanity, flamboyance, greed and silliness. It makes a Monty Python farce look tame. I'm a Doctor of both Creative Writing and Manufacturing and Mechanical Engineering, a novelist, a technologist, and still an amateur in much else.

I'm a Doctor of both Creative Writing and Manufacturing and Mechanical Engineering, a novelist, a technologist, and still an amateur in much else.